觀點

Donald Low:Hong Kong needs to rethink its super-connector strategy (part 2)

【明報文章】The Covid-19 pandemic forced Hong Kong to choose between its connections with the mainland and its connections with the rest of world. Rightly or wrong, it prioritised the former over the latter. But because China’s zero-Covid policy was (increasingly) misaligned and out-of-sync with global norms and best practices, Hong Kong increasingly found itself perceived (and labelled) as “just another Chinese city”.

Being a super-connector has reduced Hong Kong’s policy space and its international character

More so than the National Security Law, zero-Covid did considerable harm to Hong Kong’s reputation as an international city. It also showed how maladaptive the Hong Kong government had become. As the virus evolved to become more transmissible and less deadly, and as the rest of the world adapted to live with the virus, Hong Kong’s persistence with draconian zero-Covid restrictions – even after Covid-19 had become endemic in Hong Kong in early 2022 – demonstrated to the rest of the world that policymaking in Hong Kong had become less pragmatic and evidence-based.

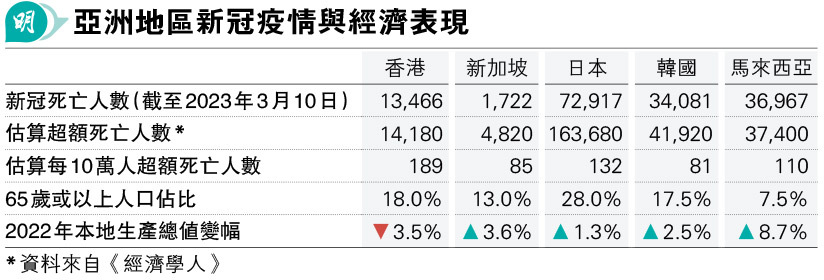

Zero-Covid also produced disastrous consequences for Hong Kong: it neither saved lives nor protected the economy (see Chart). Compared to other jurisdictions in East Asia, Hong Kong has had more excess deaths during the pandemic, even as it delayed its economic recovery unnecessarily.

Zero-Covid inflicted more trauma on Hong Kong’s economy than NSL has. At the height of zero-Covid madness in early 2022, tens of thousands of professionals in the business and financial sectors left Hong Kong – many to Singapore. As some of my mainland friends in Singapore recently told me: It took the British 150 years to make Hong Kong an international financial centre; it took the Chinese only two years (2022 and 2023) to make Singapore an international financial centre.

And the trauma would continue to recur, not least because the Hong Kong government has not convened an independent inquiry on its handling of Covid-19. Without such an inquiry, the authorities would not have the opportunity to learn from their mistakes, businesses would persist in their belief that the quality of policymaking has deteriorated, and residents would remain sceptical and cynical of the government – deepening Hong Kong’s existential crisis. By contrast, there were three independent inquiries on the handling of SARS by the Hong Kong authorities.

Avoiding stasis, inertia, and blind optimism

In many of the Hong Kong government’s public pronouncements and messages, there is a tendency to blame external factors for Hong Kong’s problems – high interest rates in the US, geopolitical tensions, western efforts to contain China – while disregarding or downplaying domestic factors (e.g., China’s slowdown, Hong Kong’s USD peg, zero-Covid). While these stories may be understandable from a political communication perspective, they may hurt Hong Kong more in the long run.

First, such narratives do not do the Hong Kong people or the economy any favours. They create the impression that all of Hong Kong’s problems are created by outsiders or enemies abroad. Not only does this damage Hong Kong’s reputation as an international city, it also does not help Hongkongers understand the complex challenges the city faces in a less globalised, more polarised world. These narratives create simplistic, binary, and ultimately false stories that Hong Kong is caught in a battle between east and west, between good and evil. In so doing, they polarise society even more.

Second, these narratives may give the authorities a crutch and an excuse not to engage in a deeper, self-critical reflection of what Hong Kong needs to do to stay relevant. Why bother to change if we can easily scapegoat the west or blame others for Hong Kong’s problems?

Third, these narratives are often based on blindly optimistic predictions of China’s rise, and of the west’s decline. While this is certainly a possibility, it is by no means inevitable no matter how sincerely or strongly these beliefs are held among Hong Kong’s elites. These narratives often conflate what is desirable with what is probable. They also promote excessive optimism in the face of our problems and failings. While optimism is usually a good psychological trait, we should strive to avoid the blind, delusional optimism that the writer, Lu Xun, described so well in The True Story of Ah Q.

Rather, Hong Kong’s policymakers should seize the opportunity that the current economic malaise offers to engage in a far-reaching exercise on how the Hong Kong economy should be adapted, even reinvented for the future. Doing so would not only signal to the world that Hong Kong has every intention to remain an essential node of the global economy, but it would also give Hongkongers (more) reason to be confident in Hong Kong’s future.

Donald Low is Senior Lecturer and Professor of Practice in Public Policy, and Director of Leadership and Public Policy Executive Education, at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. This commentary is based on a talk he gave at a policy dialogue on “Hong Kong in a Polarised World: Still a Super-connector and East-West Intermediary?”

[Donald Low]